What Does a Grade Mean? Hacking Assessment Shifts the Conversation

Jul 02, 2025

Opinion

By Starr Sackstein

When it comes time to set goals with students, inevitably, there are several whose highest aspiration is to achieve an A in all of their classes because this is what the system and their parents have impressed upon them for years.

They don’t have a plan except to do all of their work and do it on time or to try harder, which isn’t terribly specific (and likely won’t help them make the mark, especially if the teacher hasn’t identified it well with clarity).

I’d be lying if I said that a part of me doesn’t die a little when this happens.

After all this time and effort helping students try to understand that grades don’t tell the real story of who they are as learners, they still want an A to make Mom and Dad happy or to get into the college of their choice, or to prove their intellectual prowess. I can’t blame them for that, but...

An A isn’t what they think it is; it’s a blatant lie masquerading as a success.

In school, to get an A, we often ask students to play a game of abiding by the rules and doing what is asked. Students achieve this A by being complicit (and sometimes by getting lucky).

It’s fair to say that most A students aren’t necessarily the brightest or most talented kids but rather the ones who are motivated and hard-working. (I’m not saying motivation and perseverance are bad things; I’m just stating that just because some kids try hard doesn’t mean they're mastering learning.)

Every teacher has a different understanding of what an A looks like, and therefore, it is often hard for students to achieve an A with all teachers because it isn’t always clear what those expectations are.

Grading makes it easy to control learning and minimizes actual growth and reflection power. It makes the school experience about arbitrary computation and less about application and synthesis.

It’s time that we reconsider (and I’ve been saying this for a while) what we value in schools, shift the control into the hands of students, and make achievement about mastery of content and skills (to be determined by ongoing conversations and reflection).

The truth is that although grades are what we know and what we have always done that doesn’t mean they are appropriate—or ever were. They solve a problem, but they don’t even do that well.

Accountability is important, but what students take away from school is more important, and when we focus too much on the grades over the learning, we send a mixed and confusing message.

Perhaps, systemically, we can start the shift to standards-based grading and then eventually to no grades, offering the opportunity to take joy in what they gain rather than worrying about how they perform on tests and their report cards.

Moms and dads out there, what you would rather: your child enjoying the learning experience and talking about what they know and can do (as well as being able to apply it to other areas of their lives) or getting that 100 that looks awesome on the fridge but doesn’t mean anything outside of a single moment in time?

Today, I’ll end with a challenge—take the test that adorns the fridge down after about a week or two and ask your child if they remember what was on it. I bet they remember the score but not the content.

If we switch the expectation away from one-time testing environments and shift toward ongoing formative assessments, the learning is continuous and connected. This should be the goal.

- How can we continue to shift the way we think about school achievement daily?

- What would that look like at your school?

- In your class?

Starr Sackstein is a recovering perfectionist who is an assessment reforming enthusiast. She is the COO of Mastery Portfolio, an Edtech Startup committed to helping schools move to standard-based communication. Additionally, she works with teacher teams to engage students in the learning process, advocate for personal growth, and effectively use student data to drive instruction.

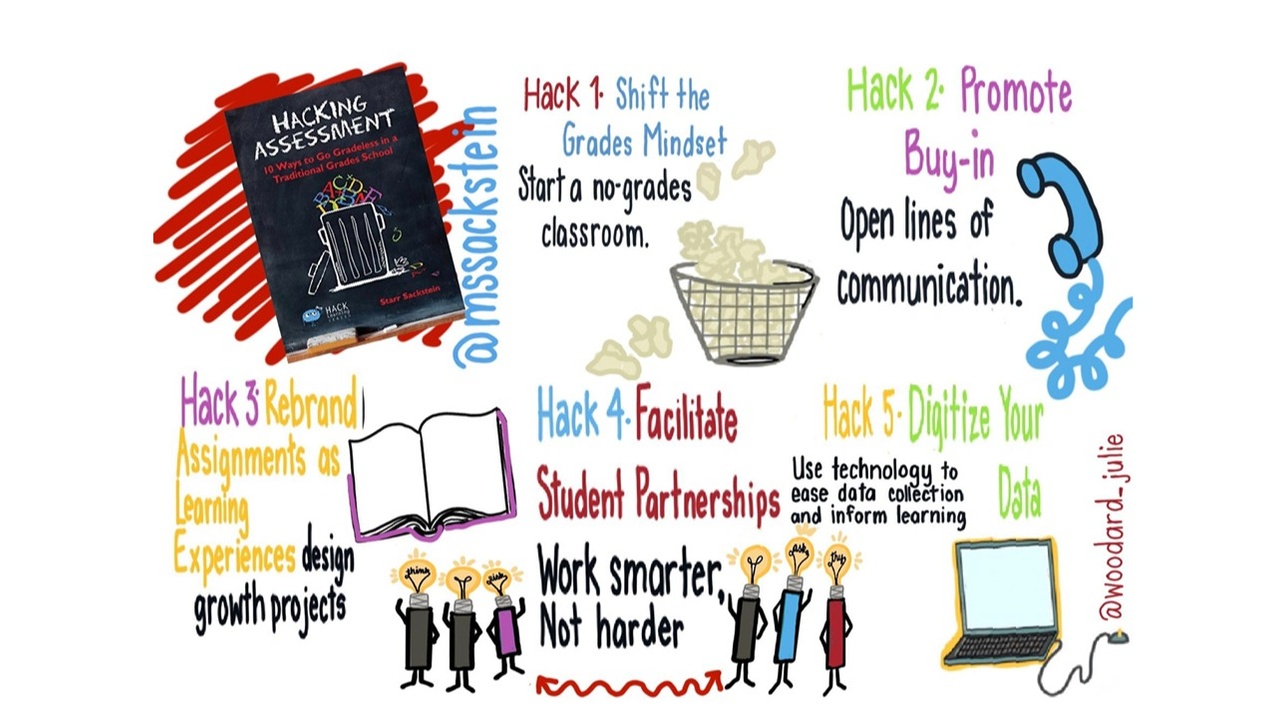

Learn more about Starr's work on her website MsSackstein.com and follow her on Twitter @MsSackstein. She is the author of Hacking Assessment Second Edition and Hacking Learning Centers. When Starr isn’t advocating for students and educators, she is a mom and partner looking for the next adventure.