Gaining Student Investment With Graphic Novels and Comics

Jun 28, 2021

Here's the problem. Many don’t see graphic novels as serious learning, or they only see the limited potential.

Author Shveta Miller, a teacher leader and global advocate for teaching with comics, sees it very differently. In her book Hacking Graphic Novels, Miller shows teachers how to:

- Guide students to look at visuals slowly with curiosity, open-mindedness, and intention

- Develop independent learners who explore the possibilities and real-world applications

- Encourage students to think, process, and express their understanding of complex systems and ideas

While comics and graphic novels are increasingly appearing on library display shelves and bestseller lists, many of our young readers still hear adults say comments like, “Choose a real book,” “That’s not real reading,” or “Try something more challenging.”

Though they may still enjoy reading graphic texts, students are internalizing the message that those books are not serious literature.

They begin to think that a quick casual flip through the text, or devouring it in one day, is entertaining, sure, but ultimately frivolous.

They aren’t exercising critical thinking and observation skills because they assume these “picture books” don’t demand that kind of attention and that intellectual nourishment comes from text-heavy books.

A graphic novel has now won the Pulitzer, the Newbery, and the National Book Award, but students and school staff alike are still hesitant about these picture-heavy novels when a class syllabus demands “rigorous close reading” of “complex texts.”

When used, the emphasis is often on their power to engage reluctant readers, bridge access to text-heavy books, or ignite an interest in reading. Therefore, the work is often focused on elements of plot and engagement without serious regard to the craft and structure.

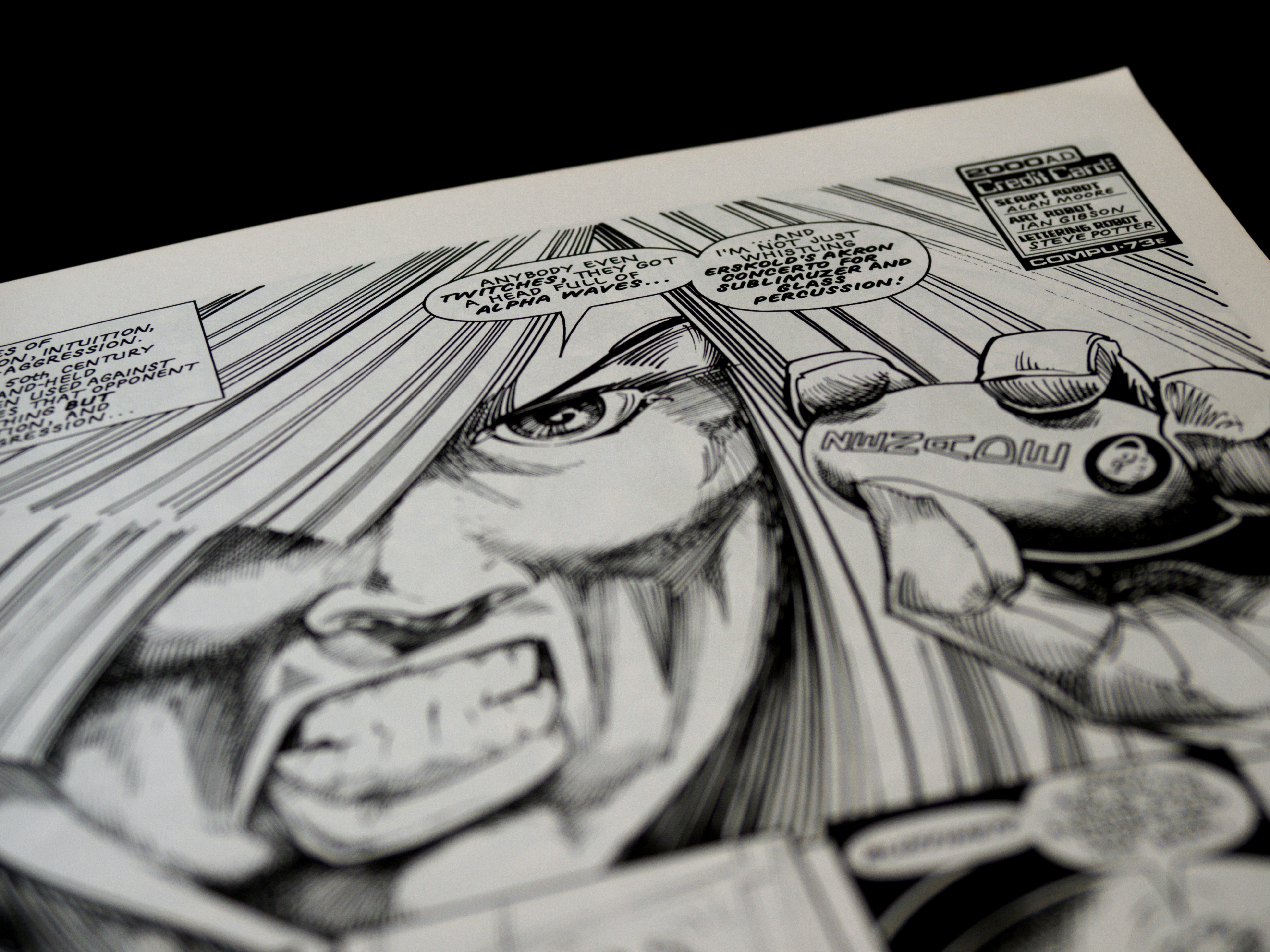

Without learning the language of comics or practicing close-reading skills unique to visual texts, students are less likely to read a graphic novel with analytical depth. They quickly consume it, overlooking the embedded complexity, unaware of how the craft and structure affect the visual story and their experience of it.

Our students have unconsciously (or consciously) adopted the view that visual texts like graphic narratives, comics, and even cartoons and advertisements do not warrant literary analysis.

They have absorbed ideas from the adults around them about the tiers of quality and purposes for different types of texts. This text is for fun; that one is for learning. I read these books fast; those take a lot longer.

Using graphic novels in the literacy classroom is an opportunity to engage students in critical conversations about canon formation and the complicated process of literary selection.

This is a chance to involve students in thinking about:

- What makes a text worthy of study?

- Who decides the value?

- What distinguishes “high” from “low” art?

- How and why have these designations changed over time?

- What role do active and curious readers play in disrupting seemingly fixed categories?

Teachers also face obstacles like censorship with graphic novels.

Betsy Gomez from the Banned Books Week Coalition and former consultant with the Comic Book Defense Fund says that images are easy targets.

One graphic novel was banned for minimalist cartoon depictions of torture. Another was censored because of incidental or comedic nudity in a few panels.

A clinical depiction of a breast self-exam led to a teacher’s firing. Innumerable graphic novels have been left out because of similar content that doesn’t usually get attacked when presented as prose.

How do we balance the values of our communities with the desire to teach students to critically engage with complex visual texts? When introducing a unit of study, we need to build investment from students, families, and the school community.

Build investment in visual storytelling

The priority is convincing students, families, and the larger school community that this is valuable work. Students benefit when we build anticipation.

Determine what they already know about reading and analyzing visual texts so that lessons are building on prior knowledge and experience. We can build from there on the inherent impulses students have when looking at visuals.

They are bombarded with visual media as they scroll on their phones, see an advertisement, view a logo on a friend’s T-shirt, and look back at the phone to see the artistic design of a new app.

We can introduce critical engagement with visual texts and frame it as essential to our students’ lived experiences.

We can show productive engagement and add value to the class’s collective learning as they sharpen skills in which they are already conversant or experts.

High school English teacher Derek Heid explains, “When you play to a student’s feeling of expertise and you just ask them to strengthen a skill that they already have, you get a lot more buy-in because now they're collaborating with you.

It's not a matter of newbie and sensei. It's a matter of two people who are meeting on common ground.”

Spark students’ curiosity about the potential to:

- Tell compelling stories

- Create subtly humorous gags

- Offer insight into a common human experience

- Shrewdly deconstruct a widely held belief

- Force us to question what we observed and our perspective

- Make us think deeply about how our backgrounds influence how we see the world

Then students can readily set intentions and precise goals. While goals and motivations will surely change, opportunities to articulate initial goals make students more likely to strive to achieve—and even exceed—them.

Students read graphic novels differently than they read prose texts, and they are often unaware of their process and strategies.

With awareness and practice, students can understand important themes, critical ideas, depth, and complexity, and they catch challenging embedded concepts.

How To Implement Graphic Novels Into Your Classroom

Step 1: Buy in yourself.

If you only teach graphic novels to engage reluctant readers, motivate students with “popular” or irreverent modern texts, or scaffold with a “gateway graphic novel,” then you may have overlooked the potential this work has to engage students in cognitively demanding analytical work.

If you assume students will be more engaged with a visual text or that struggling readers may experience more success, your instruction will not include the necessary scaffolding for engagement. Graphic narratives warrant a productive struggle.

Interpreting complex visuals, observing with care, articulating how images work, and evaluating their impact are all valuable skills, especially in an increasingly visual world. When students read digital texts, they nearly always interact with embedded visuals.

Just as all fiction novels do not have the same levels of complexity, all comics and graphic novels vary in sophistication.

Step 2: Determine the larger goal.

- Where are your students as readers, writers, thinkers, and problem-solvers?

- What have they read and built background knowledge about?

- What issues and events are impacting them?

- What reading will build schema for learning in your class or in other content areas?

- What can they read in your class that leverages funds of knowledge or intellectual curiosity?

- How can comics help them connect to concepts and information more concretely and metaphorically?

If we consider these questions when selecting texts and planning instruction, we are likely to see more engagement from students.

Step 3: Determine what students already know and what they want to know.

What questions do they have? Which topics highlight their expertise? Where can your instruction help them grow?

Step 4: Choose grade level and content area standard outcomes.

Common Core reading standards indicate that “all students must be able to comprehend texts of steadily increasing complexity as they progress through school” without specifying the texts.

They guide teachers to determine a text’s complexity and require engagement with various genres, forms, time periods, and cultures.

Nearly all English language arts standards for reading, writing, speaking, and listening apply to appropriately complex graphic novels.

Science, social studies, and math standards similarly do not dictate texts or limit students to one form of expression, but they do indicate fluent and sophisticated visual interpretation (e.g., charts and graphs, primary source documents), developing greater conceptual understanding, and representing processes and concepts in various forms and models.

Choose objectives your comics and graphic novels will address, and connect these skills and qualities to various careers. All twenty-first-century professions demand a comfort level with an increasingly diverse set of texts, visual communication models and tools, and innovative thinking.

Step 5: Identify self-created personal learning goals.

- Adjust starting points using the first written response

- Introduce the objectives as a menu of options.

- Ask students to identify which objectives they have achieved and which ones they now want to meet.

- Later, you will guide students to revisit this chart, reflect on progress, and set new targets.

In Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain, Zaretta Hammond draws on neuroscience to explain how making progress with challenging work provides a dopamine hit, motivating us to accomplish more.

As teachers, we can use our knowledge of students’ assets (strengths, interests, what they already know) to build learning capacities. When we offer the chance to set their own learning goals, we develop the necessary trust to support meaningful outcomes.

Step 6: Communicate with school leaders and colleagues.

As students engage with complex graphic texts, share the learning outcomes and artifacts. Include questions students posed, evidence they cited when explaining a technique, and the conceptual visuals they created. Explain insights you gather through viewing their work.

Creating comics and visual stories also holds instructional value. When we ask students to analyze and describe the essential elements of a complex concept, scientific system, or

If someone implies that graphic texts are not rigorous, invite them to observe learning activities.

They will see students discussing visual texts with insight, precise language, and passion, as well as posing intriguing questions about the effects of stylistic choices or an author’s purpose, articulating the subtext, and drawing rich meaning from a seemingly simplistic cartoon.